By Andrea Thompson

Holiday breaks are wonderful for many reasons, but as I return for a new year after a self-imposed hiatus, one of the benefits I reaped is getting to view D. Smith’s remarkable documentary “Kokomo City” multiple times. In the constant hustle that is the life of a freelance writer, getting to really soak in and absorb a film has become something of a luxury in the age of content, AI, and ever present deadlines.

And there is so much to appreciate in “Kokomo City,” which follows the lives of four Black trans women, all of whom are or were engaged in sex work. Want to think, consider, and laugh out loud within the first five minutes? Then give this one a watch, because there’s a whole lot of ground to cover during the 73 minutes we spend getting to know these women.

This is the part where I tend to marvel at the fact that this is a filmmaker’s feature debut, but D. Smith had been working in the music world as a producer for years before she discovered a passion for filmmaking, an endeavor which was partly born out of necessity. Although she worked with household names in the early 2000s that included Lil Wayne and Ciara, among others, even winning a Grammy in 2009, she was “forced out of the music industry” (as Smith herself put it) once she came out as trans.

Finding herself broke, homeless, and somewhat adrift, “Kokomo City” isn’t just representative of a promising new direction, it’s something of a comeback, and the accolades have been pouring in. They damn well should be, since Smith makes good use of the access she was granted to each of these women’s lives, the kind it’s difficult to picture another filmmaker getting.

If Smith weren’t also Black and trans, would we have been privy to Smith’s own very individualistic take on the contemplative route, with the kind of intimate dialogue that includes everything from hair removal tips to discussion of class, race, and how such forces affect their ability to pay those bills while they’re lounging in bed or the bathtub?

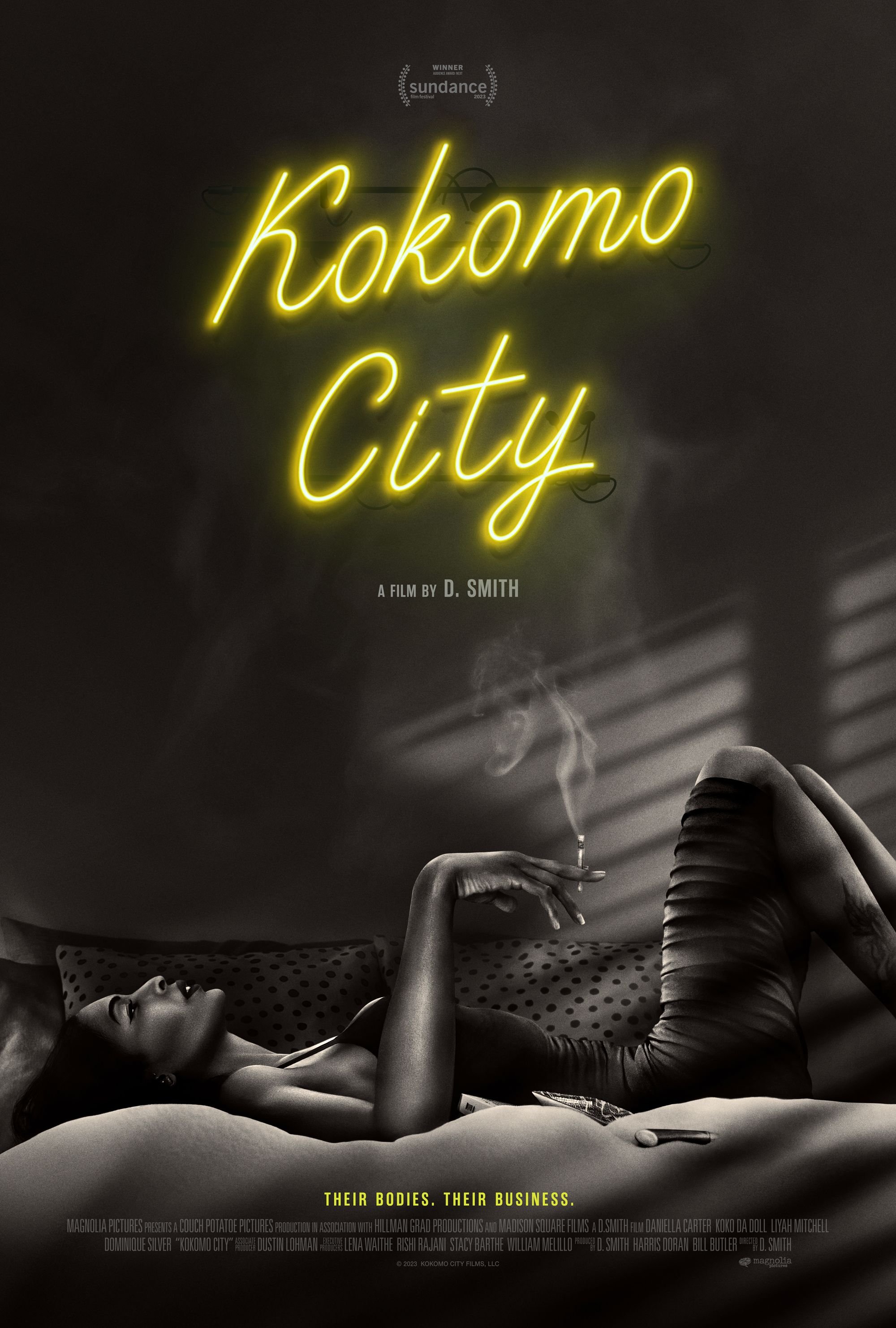

Unlikely, since “Kokomo City” has, in many ways, an insider’s unblinking gaze of the world and topics it’s delving into. And although her previous career came to a painful end (for now at least), it seems to have been time well spent, with the doc’s gorgeous black and white aesthetic and stylistic flourishes giving it an edgy music video feel - the click of a gun, the sound of a roar as sexuality is discussed, and the killer use of music in general.

Those discussions about sexuality, complete with light reenactments and nudity, also come off as both naturalistic and raw, to use the most convenient cliche. But that rawness applies to other less flashy, but still arresting topics, namely the way all four women discuss their lives and how their identities affect not only their daily circumstances but those of their clients. These women are older - to use the more gentle euphemism about anything having to do with women in pop culture who’ve left their 20s behind - having successfully entered various phases of their 30s, and are thus savvy survivors; not only more aware of the bullshit but less likely to take it.

That bullshit manifests in film’s most constant thread: the vicious hypocrisy of the many ways men take advantage of and sometimes actively harm them, and how cis women are typically all too willing to let it happen, but are likewise unable to imagine their partners even being attracted to them. And all four of the film’s subjects, as well as the men who are willing to speak of that attraction, are willing to make some truly jaw-dropping statements about it.

Daniella Carter in KOKOMO CITY, courtesy ofMagnolia Pictures

As one member of the film’s central foursome Daniella Carter sums it up: “The only thing he there for is escaping his own goddamn reality. And you know what that reality is? Ten times better than the one he’s giving you.” With such statements - and plenty more where that came from - it would be easy to think that “Kokomo City” revels in self-seriousness, but like many a pop culture offering from those who are traditionally marginalized, humor and joy are the primary defense mechanisms when you generally don’t have access to more official protection.

What’s left unsaid may be even more telling. How did the men who are willing to talk about homophobia in the Black community and their own attraction and encounters with trans women come to meet Smith and the other women on-screen? As the women themselves speak of how often their typical customers conform to the stereotypical tough guy image, it’s indicative of a long history of gender and sexual fluidity in hip hop, a community that has only recently begun to grapple with its history of vicious homophobia.

It doesn’t prevent “Kokomo City” from earning every bit of the oft-used descriptor unflinching, and sadly that includes a frustratingly common ending for one of the most jaded of the women the documentary follows: Koko Da Doll, who was shot and killed in Atlanta, and to whom the film is dedicated. If another piece of art must end up being a tribute to a vibrant, resilient person whose life still ended far too soon, this one at least is also a beautiful, powerful testament to a community which finds itself under siege yet nevertheless refuses to define itself by its oppressors.