How this process is portrayed sets the tone. Just four years prior in “The Silence of the Lambs,” a man feminizing himself was depicted as the ultimate horror, but as the central characters delightedly, carefully adorn themselves with makeup, wigs, stockings and all around style, director Beeban Kidron likewise relishes their joy and the care that goes into it. It’s indicative of the movie’s respect, not just for femininity, but women in general.

Critics might have accused “To Wong Foo” of timidity, political correctness, and a lack of originality in terms of plot, and they weren’t completely wrong. There’s a certain suspension of disbelief required, not just for the over-the-top, utopian ending, but that almost none of the residents of Snydersville, the small town Noxeema, Vida, and Chi-Chi become stranded in, recognize them as men in drag.

No, “To Wong Foo” couldn’t be accused of diving too deep. But it does mostly accomplish what it set out to do, which is be funny as hell. Snipes, Swayze, and Leguizamo are all in top form, and it’s not only the jokes that land perfectly, it’s the banter, which ranges from tough love to outright animosity, and finally, to camaraderie.

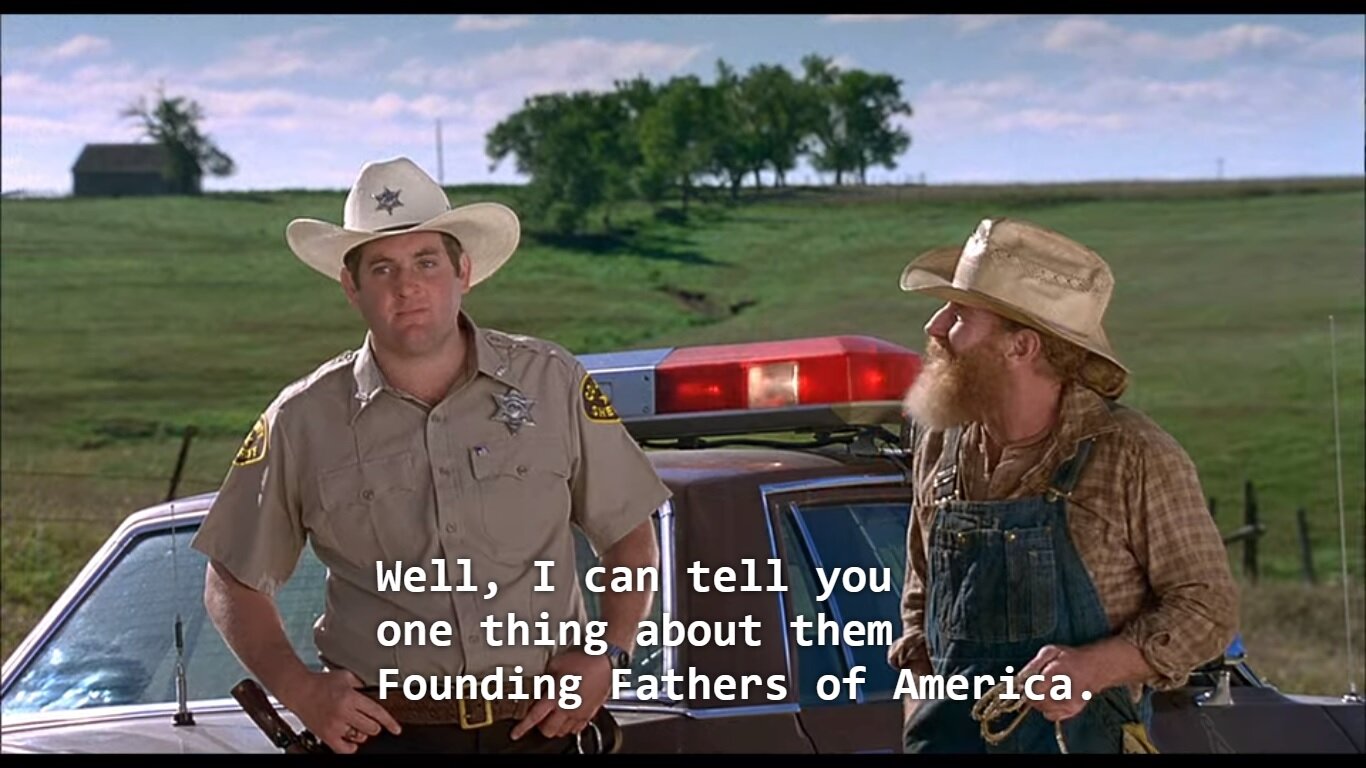

It’s also not as if the movie is unaware of the very real danger these three face on a daily basis. They only become stranded in Snydersville in the first place because a sheriff attempts to assault Vida one night after he pulls them over. She fights him off, but believes she kills him in the process rather than merely knocking him out, causing all of them to flee in terror. That terror is also present from the moment their encounter with him begins, when Sheriff Dollard pulls them over while they’re driving in a remote area at night. As he comes up to them with his hand firmly on his gun we know is going to be unpleasant at the very least. The only question is whether it will also be horrific.

Thank goodness not all small towns are completely hellish, because while Snydersville proves to have the kinds of characters who benefit from the trio’s presence, it has its share of dangers as well. At one point, Chi-Chi gets harassed from a group of male rednecks in an encounter that threatened to become a gang rape, only to be saved by a nice local boy who actually becomes her love interest.